One in a series of short pieces demonstrating the diverse research in gender and feminist geographies. To comment or to write a post yourself, please contact our Web Coordinator, Louise Rondel at l.rondel@gold.ac.uk We welcome posts by all members of the GFGRG.

I recently had what my best friend now calls ‘my Baltimore rant’ on Facebook. Having grown up in the suburbs of Baltimore, many of my friends from High School and University moved from the ‘burbs to live in this rapidly changing city on the east coast of America. Many of you will know Baltimore from The Wire, and your impressions of the city, portrayed in this gritty urban drama, will not be unfounded, with concerns about recent trends in rising crime rates being reported by international papers like the New York Times.

The rant stemmed from a recent Facebook post from an old friend that caught my eye. He and his wife had moved from the outskirts of northern Virginia, an area that has become increasingly expensive in the past decade, and had taken advantage of a new scheme in Baltimore called ‘Vacants to Value’. At first I was curious – the pictures of the row house he had bought certainly seemed run down – he had lived in a gated apartment block with a pool the last time I had seen him. This run down building seemed a bit unusual. And then I realized he had actually bought two row houses. And was building an enormous house from these vacant properties with the help of the scheme, breaking through the two houses to create a new, very beautiful and tastefully designed home for his growing family.

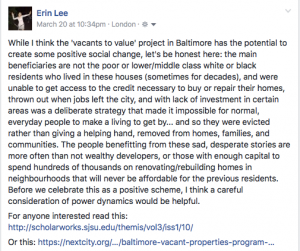

I started looking into the details of the scheme, and realized that these houses were not simply vacant. They were vacant for a reason. And then I had my rant.

Perhaps my rant was unfair – as it clearly implicated my friend, who had benefitted from the poverty and devastation of the black community in Baltimore. Indeed, my ire was less about my friend, and more about a policy that has allowed the already middle-class to take advantage of such schemes. Having grown up in a single-parent, working-class family, we didn’t have enough money to buy meat at the supermarket, or new clothes from department stores (shopping at the local thrift store for most of our clothing), but my prudent, hard-working mother was able to buy her own house after a decade of saving with the help of a grant from the Department of Housing and Urban Development. While HUD has continued to help some of the poorest Americans buy houses over the past years, it looks as if the Department will be gutted completely under Trump, meaning that those with the requisite capital are now able to take advantage of schemes that reinforce the growing gap between the rich and the poor, while the poor are screwed.

My college degree, paid for in large part by the largesse of the federal government (a luxury that students from low-income families like myself no longer have) has allowed me to climb that ever-more-elusive social ladder to the middle class. I have the privilege of a permanent full-time post in a wonderful academic institution in the UK, I own a car and a house (with a mortgage) in London. I live with my partner, who came from a small rural village in Ireland, from a family with a small cattle farm, whose mother knitted sweaters on a loom in their home to make extra money for their family of four. We eat pesto and smoked salmon (things neither of us had ever heard of growing up), and have prosecco at dinner parties (something we had never tried until our mid-twenties). We are now firmly, solidly middle class and we have profited from the changes to the area of north London where we live, an area that is also being gentrified.

Yes, I almost certainly benefit from the increasing money being spent on tearing down social housing in my area, and from the new flats that seem to appear almost overnight. Many of us writing about gentrification often benefit from these changes, either through increased house prices in areas that we could afford before gentrification started (but would not be able to buy, or even rent now), or through enjoying spaces in the city that have been created specifically for those privileged enough to be earning a middle class salary (even if we don’t consider ourselves to be middle class). But we have a responsibility to push back, through research and teaching, and through talking with friends (without ranting directly at them) about social issues and poverty. The findings that characterize almost all the research I have conducted over the past decade – mostly with marginalized communities in England – have had a unique commonality that exacerbates violence, isolation, and social stigma: poverty. My work suggests that a sustained lack of public sector funding for issues that overwhelmingly affect the most deprived communities is creating an increasingly unequal society. Those in the poorest areas are the most at risk, and whether we are talking about gentrification in London, or Vacants-to-Value in Baltimore, those with sufficient modes of capital must push back against policies that allow the process of gentrification that further marginalizes the already marginalized. Through these means (amongst others) we can try to make some small difference.

Dr Erin Sanders-McDonagh is from the School of Social Policy, Sociology and Social Research, University of Kent.

Contact: E.Sanders-McDonagh@kent.ac.uk