GFGRG Undergraduate Dissertation Prize

Run Like a Girl: The Digital Reinforcement and Deconstruction of Gender Norms by Female Running Influencers on Instagram

Francesca Willn, University of Exeter

Undergraduate Dissertation Prize 2025 – Runner Up

GFGRG Travel Grant

Reflections from the RGS-IBG Annual Conference 2025

Gráinne Fay, University of Nottingham

Travel Grant 2025 – Recipient

GFGRG Travel Grant

Exploring Endocrine Geographies: Reflections from the 2025 RGS-IBG Conference in Birmingham

Jay Sinclair, Durham University

Travel Grant 2025 – Recipient

RGS-IBG Conference 2025

Creative feminist theories and approaches to energy geographies

Giulia Mininni, University of Manchester

RGS-IBG Conference 2023

Reflections from the RGS-IBG Conference 2023

Poppy Budworth, University of Manchester

RGS-IBG Conference 2023

Taking Care: Navigating the RGS Annual Conference as Feminist Geographers

Poppy Budworth, University of Manchester

GFGRG Undergraduate Dissertation Prize

Publication to Protests: A Geographical Exploration of Power and Resistance in The Handmaid’s Tale

Georgia Silva, University of Nottingham

Undergraduate Dissertation Prize 2020 – Winner

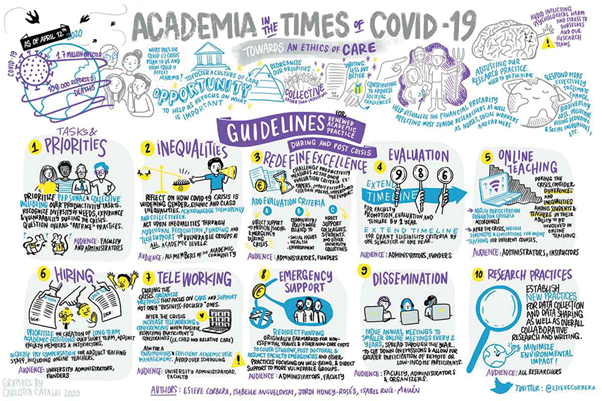

GFGRG Blog

Academia in Covid-19 times: Reflections on practice

Anonymous; Sawyer Phinney; Esteve Corbera, Isabelle Anguelovski, Jordi Honey-Rosés, Isabel Ruiz-Mallén

GFGRG Blog

Research on women’s experiences of misogyny in Greater Manchester

Jess Bostock, University of Manchester