GFGRG dissertation 3rd prize winner

Bronwen Butler, UCL

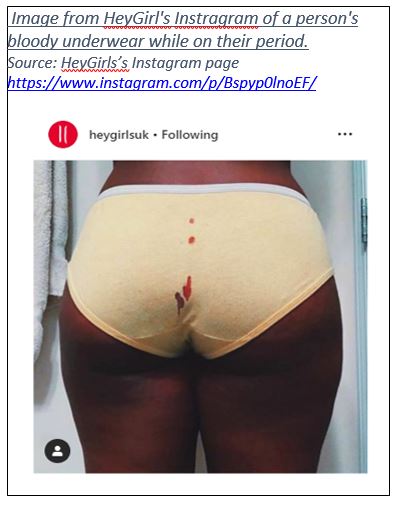

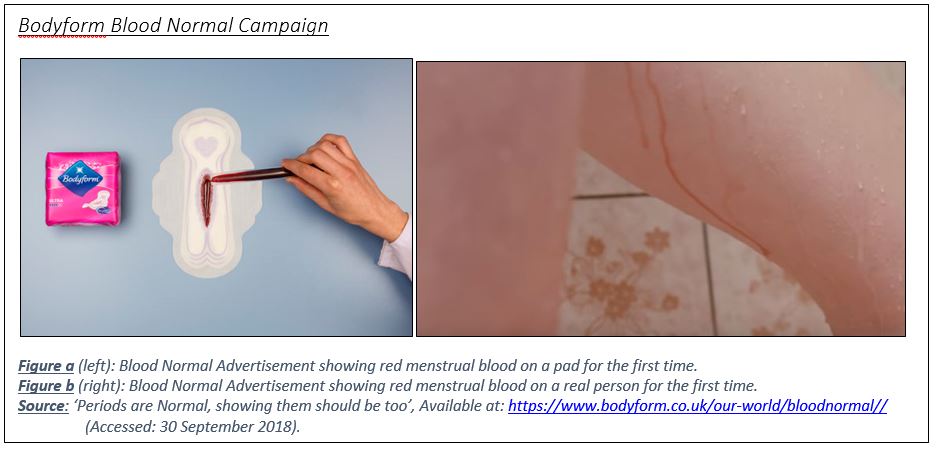

Menstruation, somewhat unexpectedly, has become a high-profile issue in the UK over the last couple of years. From ‘the pink protest’ outside the Westminster Parliament in December 2017 to Bodyform’s advert campaign #bloodnormal, from tampon selfies and campaigns against the luxury taxing of tampons, to a day dedicated to menstrual hygiene, menstrual issues have been firmly put on the map. Now, a growing number of charities and social enterprises, such as, Bloody Good Period, #FreePeriods, the Red Box Project, The Homeless Period, Hey Girls and Freda have all coalesced around a fight against what is termed ‘period poverty’ – a lack of access to menstrual products due to financial constraints. Even certain multinational companies, such as Procter and Gamble’s Always who launched their #endperiodpoverty campaign in March 2018; are promising consumers that they can help bring menstrual products to women and girls who cannot afford them.

The UK seems to have taken hold of such actions under the phrase ‘period poverty’ and a surge in conversation among activists, media outlets, companies and politicians, utilising this term. It has subsequently been debated in parliament where Labour MP Danielle Rowley declared to the House of Commons ‘I am on my period’ and spoke about her experience as a woman on her period to highlight the issue within the UK. Furthermore, after outcry around period poverty across social media, supermarkets like Tesco have reduced the cost of menstrual products by five percent to cover the cost of the once 20% ‘Tampon Tax’ (Tesco PLC, 2017).

My research centres around the term ‘Period Poverty’ and the recent proliferation of this idiom in the United Kingdom. Much of the geographical and sociological research completed so far around the ideas contained in the phrase ‘period poverty’ have been within the context of sanitation in the Global South (Thorton, 2013; Jewitt & Ryley, 2014). While in both this, and the UK context, social problems around menstruation are symptomatic of patriarchal induced taboo, I noticed that the ‘Period Poverty’ proliferating media in the UK was portrayed in a distinctly different way to the Menstrual Hygiene issues of the Global South and therefore felt it merited attention in its own right.

This research is situated as part of a growing crop of critical feminist geographies that explore the power behind discourses affecting gendered inequality, like that of shame and taboo in menstrual discourses. I explore ‘period poverty’ as a counter-discourse to typically entrenched representations of both menstruation and women.

The effects of period poverty are a clear example of how gendered geographies of the everyday can produce and reinforce social inequalities and therefore this term needs to be investigated in its various contexts. I analyse ‘period poverty’ in these contexts; its development through research; use by advertisers and use activists in creation of a movement of menstrual activism. I situate this work as part of a growing crop of critical feminist geographies that explore the power behind discourses affecting gendered inequality, like that of shame and taboo.

I use a multi-sited critical discourse analysis to dissect the work that the drive around ‘period poverty’ has done in challenging patriarchal power, by revealing a symptomatic silence, and confronting social norms around menstruating women’s’ bodies. I trace the work of this term throughout research, advertising and popular media. Throughout this dissertation I explore what work ‘period poverty’, as a concept, does in enabling mainstream conversation of a taboo subject. How it challenges the history by which menstrual taboo has been reinforced. How period poverty differs to discussions of Menstrual Hygiene Management; and the work period poverty does in assembling a powerful alliance for the visibility of menstruation/menstruating bodies.

My first section uses Plan International UK-based period poverty

research to understand the production of ‘period

poverty’ as a category. The research they undertook brought the issues of

period poverty in 21st Century Britain into the public consciousness

(Russell & Smith, 2018: 4). This is to understand the evolution of period

poverty and the extent to which the work under ‘period poverty’ deviates from

‘Menstrual Hygiene Management’ discourse commonly seen in Development

geographies. In the following chapter I analyse the embodied politics of

web-based brand-generated promotional contents. The historic silencing of

menstruation in mainstream culture limits visible cultural representations of

menstruation to menstrual product advertising. Advertising reaches huge audience and holds incredible power to

spread stigma or inform/empower watchers. I dissect advertisement

representations in order to understand how period poverty is characterised by

the wider media. This section looks

to the gendered representations within advertising and patriarchal induced

censoring. It unearths the extent to which ‘period poverty’ has contributed to a

transition in menstrual product

advertising.

The final chapter uncovers how a popular movement has arisen in 21st century Britain to tackle a lack of access to menstrual products and the taboo that has caused this issue to go relatively unnoticed until recent years. Here, I explore the embodied politics of ‘period poverty’ as a movement. This is to understand what work this phrase does in assembling a powerful alliance of menstrual activism to combat taboo and gendered inequality. In order to complete a picture of period poverty I ascertain the extent to which it is part of a broader societal, liberal feminist movement and provides new visibility for a counter-discourse around all menstrual issues.

My analyses allow for a few grounded conclusions: I contend that ‘period poverty’ is a politicised term and category that differs from menstrual hygiene management and from other forms of menstrual activism. While, ‘period poverty’ has been used to some extent as a promotional device and can replicate development discourses of menstrual hygiene or the ‘girling of development’, it has done much politicalised work in creating a counter discourse to the menstrual taboo that reinforces gendered inequality.