As a group of feminist researchers we thought it pertinent to provide our reflections on how our current practices are being impacted by Covid-19 and the uncertainties surrounding the new conditions in which we find ourselves. The views posted below are individual reflections on one’s own circumstances. In publishing these, we hope to create a sense of solidarity around the struggles that some researchers are finding themselves immersed in.

Reflections

Anonymous

“The middle of March was the last time I went to the swimming pool, it was independent study week and it was my 27th week being pregnant. It was about that time that the government in the country of the satellite campus I work for decided to implement distance learning for all education institutions. That early decision in comparison to what was happening in the UK insilled me with a sense of confidence that I would be looked after. Of course, it was a struggle to get online distance learning up and running at such short notice, but I suppose I quite enjoyed it. The students appeared to take it in their stride and all was good.

The the home campus extended deadlines by two weeks, and this meant that I could not take my leave as I had been previously planning (I should point out that I had meticulously planned conception so that if all was well the baby would arrive after term), as who would do my marking? I, of course, stressed this, but everybody appeared to have their own issues that needed dealing with, and the lack of support was quite obvious to me but not to anyone else. Borders were closed everywhere and I had to find a new doctor. The water birth I had planned went out the window due to new policies, and I began to get incredibly homesick watching friends have their families visit in weird and wonderfully social distanced ways to see their newborns.

I knew that having a baby would be difficult to juggle with academic life, I knew it would be hard to do away from friends and families, in a place where the health care is great but not always logical to me, but I didn’t know it would be this hard. I want to go home, I want to go on leave, I want to go to prenatal Pilates, antenatal classes with my partner, I want a water birth without a mask… When you read the birthing books it appears that giving birth should make you feel empowered, I don’t and I am not sure any of us do in amongst this pandemic”.

Barriers for Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Students During COVID-19

Sawyer Phinney, University of Manchester

The COVID 19 pandemic has disrupted lives around the world, including those of many marginalized people, who unexpectedly face added burdens and vulnerabilities. The impact of COVID 19 is particularly challenging for transgender and gender non-conforming communities.

In the middle of my PhD at the University of Manchester, I decided that I wanted to start hormones and begin my transition after internalizing and suffering from gender dysphoria for most of my life. I was nervous, anxious and utterly afraid to do this during my studies as I was unaware how staff and other students might react and if it could jeopardize my safety, and my career in academia because of it. When I looked through my university’s website, I was disappointed but not surprised to find very little resources for trans and gender non-conforming PhD students.

I first visited my GP in June 2019 to consult about my gender dysphoria and starting hormones. My GP explained the process to begin my journey and that I would need to be referred to an NHS Gender Identity Clinic (GIC) that would take several appointments with gender-specialized therapists that would deem me ‘fit’ enough to begin testosterone. My GP also mentioned the waitlist for the initial consultation was now over three years, and it could be nearly four until I could start hormone therapy. Dysphoria is not easy to deal with, and especially to finally muster the courage to openly discuss it with your GP, only to be told that my transition would have to wait many years.

Trans and gender non-conforming people face difficult barriers to access healthcare, from GP and medical professionals lack of training and in some cases, discrimination and refusal of care, to gatekeeping protocols to funding cuts. Due to decades of Tory government austerity and transphobic health care practices, funding has been cut to Gender Identity Clinics (GICs) and nearly half have closed down over the last few years.

As other trans and gender non-conforming folks in the UK, many of us have been forced to seek hormones and gender-affirming care in private clinics or the black market, paying out of our own pocket and going into debt because of it. In the UK, hormones can cost £100 per month through a private clinic. So, in other words, if you have some money, you can bypass the barriers of GIC clinics. This has created a two-tier system of those who can afford to pay to seek care from private gender clinics and those who cannot.

As a PhD student living on near poverty wages and working precariously, this has posed serious financial challenges that have only been exacerbated by COVID 19. The threat of job losses, hours, and the reduction of teaching assistant positions announced by UK universities places many trans and gender non-conforming students, like me, at risk who heavily rely on teaching and/or research assistant income to pay for hormones and gender-affirming care, such as medical surgeries. Other folks have had their surgeries or gender-affirming care delayed or postponed due to the virus, or because of loss of income, have had to reschedule for a later date. Statistics show that 90 percent of transgender people do not have access to a formal job and the assistance measures taken by many countries support unemployed people. Therefore, many LGBTQ people who are not part of the formal economy, are left out of government employment aid without the possibility to earn income. Moreover, some trans and gender non-conforming students may not be able to access health care and hormones at all due to closure of clinics and medical providers prioritizing COVID-related care. This can pose serious challenges to mental health contributing to increasing gender dysphoria and can be particularly stressful for gender non-conforming and trans PhD students who are forced to pause their hormone therapy or cannot access needed medical and psychological care.

The UKRI recently published an equalities impact assessment for PhD funding extensions in light of COVID 19. The impact for trans students (who they list as ‘gender reassignment’) is reported as ‘unlikely’ because trans and gender non-conforming students ‘schedule to transition’ upon the completion of their PhD. This assumes trans health care is readily made accessible in the UK and it is overtly obvious that they failed to consult or speak to a single trans or gender non-conforming student for this assessment or they would have been privy to the reality that transitioning does not happen on a scheduled date and in a vacuum.

Part of my transition will involve top surgery. I was lucky to find a surgeon through a private clinic in Germany to do this at an affordable rate (still costing me thousands of dollars), arranged to take place in September 2020. Although I have been saving funds from the wages that I was making as a teaching assistant over the last year and a half, my university recently announced that teaching assistant positions and hours will be reduced significantly next fall in light of COVID 19, and as many other PGR students transitioning, I am uncertain if I will be able to meet the costs to pay for my surgery.

I call on all universities and research funding bodies to assess the unequal impact of COVID 19 on trans and gender non-conforming PGR students who cannot access or afford care and provide needed support through funding and additional extension during these times.

We have been told repeatedly that this virus is a great leveller, that it does not discriminate; but it does. The death rate from the disease is twice as high for men as women, Black men in the UK are 4.2 times as likely to be killed by the disease than white men of the same age, Black women 4.3 times as likely as white women. Disable and chronically ill people are not only at higher risk of death from the virus itself, but also as a result of the institutionalised ableism in health care policy and medical ethics. COVID-19 has hit the most deprived neighbourhoods and the most deprived people hardest. Inequality has shaped the pandemic, its course through the country and responses to it.

Our ability to adjust to the pandemic, to protect ourselves or to find a ‘new normal’ is unequal too. Women and young people have been most likely to lose paid work, low-paid workers in personal services most likely to have to continue working, in close contact with others, often without adequate protection. People with the highest incomes (disproportionately white men) are the most likely to be able to work from home and to have the space and equipment to do so. Staying home is not the same for a household with a big house and garden as it is for a large family in a small flat. COVID-19 and the social response to the pandemic have caused population-level anxiety, which is being experienced variable ant the individual level. We are perhaps in the same storm but different in boats. In the UK domestic abuse helpline have risen by 49 per cent and charities assisting vulnerable families have seen an exponential surge in demand for their services. In India the ‘world’s most dangerous country for women’, the scale of domestic violence has escalated to such an extent that the National Commission for Women (NCW) has launched a Whatsapp service in addition to supporting online complaints. These examples show the need to examine and understand how the geopolitical dimensions of the pandemic are impacting individual’ homelife and how homelife is also characterising individual experiences of the pandemic (see Brickell 2012). For some this will be a period of deep trauma and we may only learn the extent of what people have suffered over the years to come.

For academics these inequalities have been felt in the threat of job losses and cut hours for casualized staff, PhD students coming to the end of their studies face bleak prospects for employment in universities, or elsewhere, while staff and students with caring responsibilities have seen demands on their time multiply. Unsurprisingly, women are doing the majority of the increased childcare and housework that lockdown has brought, with domestic pressures even greater for parents of disable children with complex care needs, who have lost access to respite and other support services. The effects of this are measurable in a reduced ability to do research, to write and to publish – the things that ‘count’ for promotions and job security. Around the world, as universities move their teaching online, existing inequalities are being strengthened and social and gender divides between students are widening.

This virus is not an equaliser, it does discriminate. We call on universities and other actors in Higher Education to monitor and ameliorate this discrimination. Covid-19 could undo decades of work towards equality within the academy, we must not let this happen. Instead, we can use this opportunity to imagine a new future, where the value of caring is recognised, work is flexible and the environmental gains of our new ways of working continued. We could embrace an ethic of care within academia, redefine what is important, and build an academic world that is sustainable, caring, and respectful to all.

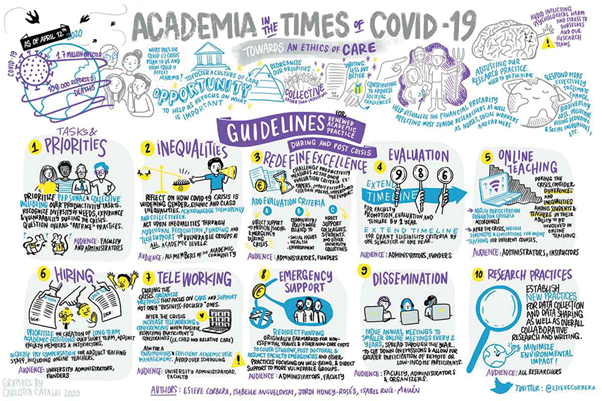

Academia in the Time of COVID-19: Towards an Ethics of Care

Esteve Corbera, Isabelle Anguelovski, Jordi Honey-Rosés, and Isabel Ruiz-Mallén

Abstract: The global COVID-19 pandemic is affecting people’s work-life balance across the world. For academics, confinement policies enacted by most countries have implied a sudden switch to home-work, a transition to online teaching and mentoring, and an adjustment of research activities. In this article we discuss how the COVID-19 crisis is affecting our profession and how it may change it in the future. We argue that academia must foster a culture of care, help us refocus on what is most important, and redefine excellence in teaching and research. Such re-orientation can make academic practice more respectful and sustainable, now during confinement but also once the pandemic has passed. We conclude providing practical suggestions on how to renew our practice, which inevitably entails re-assessing the social-psychological, political, and environmental implications of academic activities and our value systems.